Introduction:

Normal cardiac function relies on the intricate three-dimensional (3D) microstructure of cardiomyocytes, which undergoes fundamental pathological remodelling in heart disease, leading to functional impairment. However, significant experimental and computational challenges hinder the reliable and efficient 3D microstructural analysis and quantification. Thus, current approaches often rely on inferring 3D information from 2D images, but this simplification may result in substantial erroneous conclusions. To overcome this problem, we developed a robust sample preparation protocol for high-resolution microscopy, which, combined with an optimised artificial intelligence-enabled toolkit for image restoration and segmentation, allows for the efficient analysis of 3D cardiomyocyte cytoarchitecture within ventricular myocardium.

Methods and Results:

We tackled four key challenges in our toolkit: sample preparation and imaging, image restoration, automatic segmentation, and semi-automatic proofreading. Improved sample preparation comprises passive refractive index matching, extended staining times, and controlled humidity during sample mounting. This produced high-contrast images of cardiomyocyte boundaries to depths of up to 250µm in seven species (mouse, rat, rabbit, pig, horse, elephant, human) using a range of different fixation conditions. Noise and spatially variant blur in confocal microscopy stacks were reduced by an AI model that was trained on matched image volumes with varying laser power and confocal pinhole sizes. On withheld test data, our best image restoration network reached a normalised mean squared error of 0.005±0.001 and a structural similarity index of 0.71±0.03, significantly reducing noise and restoring sharpness. For automatic 3D segmentation of individual cardiomyocytes, we evaluated five approaches on a 3D dataset of 73 stacks with diverse experimental conditions, including myocardial infarction and ex vivo tissue culture. The best automatic cardiomyocyte segmentation workflow achieved an adapted Rand error of 0.06±0.03 on the test set. Additionally, we introduce a semi-automatic workflow, which can be used to error-correct the automatic methods or generate reconstructions from scratch, reaching a fast throughput of three cells per minute on a challenging, previously unseen dataset.

Conclusion:

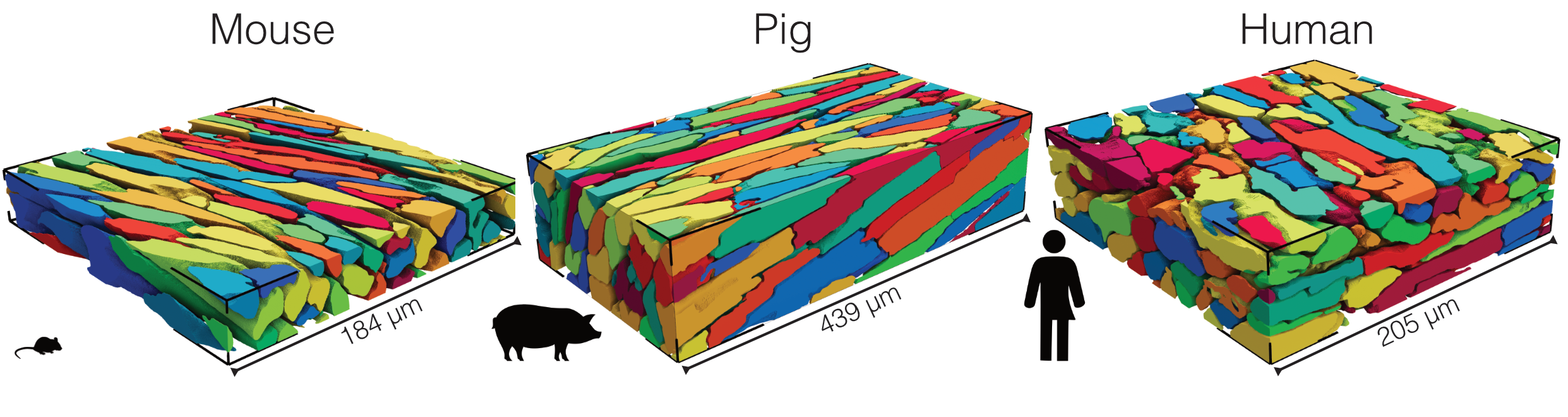

In summary, we have developed a comprehensive and accessible toolkit for the exploration of 3D cardiomyocyte microstructure. The data and the toolkit are openly available, and the semi-automatic workflow is accessible through a dedicated graphical user interface. Given the size and diversity of our dataset (seven species, data from multiple labs and microscopes, including diseased tissue), we expect our methods to perform robustly across species and experimental conditions, enabling large-scale efficient analyses using 3D models of ventricular myocardium. High-resolution 3D cardiomyocyte reconstructions can be used for a host of research questions, including characterisation of diseases (e.g. hypertrophy, gap junction reorganisation) and in silico modelling.

Figure: Examples of artificial intelligence-enabled 3D cardiomyocyte reconstructions from confocal microscopy image volumes acquired from mouse, pig, and human ventricular tissues. Manual segmentation of shown stacks typically requires days to weeks of focused effort.