Background:

Pregnant healthcare professionals in cardiac electrophysiology (EP) labs may be exposed to ionizing radiation during fluoroscopy-guided procedures. Despite strict international fetal dose limits, real-world dosimetric data remain limited. In many countries, pregnancy still poses a professional barrier—especially in the male-dominated field of EP—despite modern technologies enabling safe procedures under rigorous radiation protection.

Objective:

To quantify occupational radiation exposure in a pregnant EP cardiologist during the first two trimesters of pregnancy, over a four-month period, while working in a lab adhering to ALARA (As Low As Reasonably Achievable) principles.

Methods:

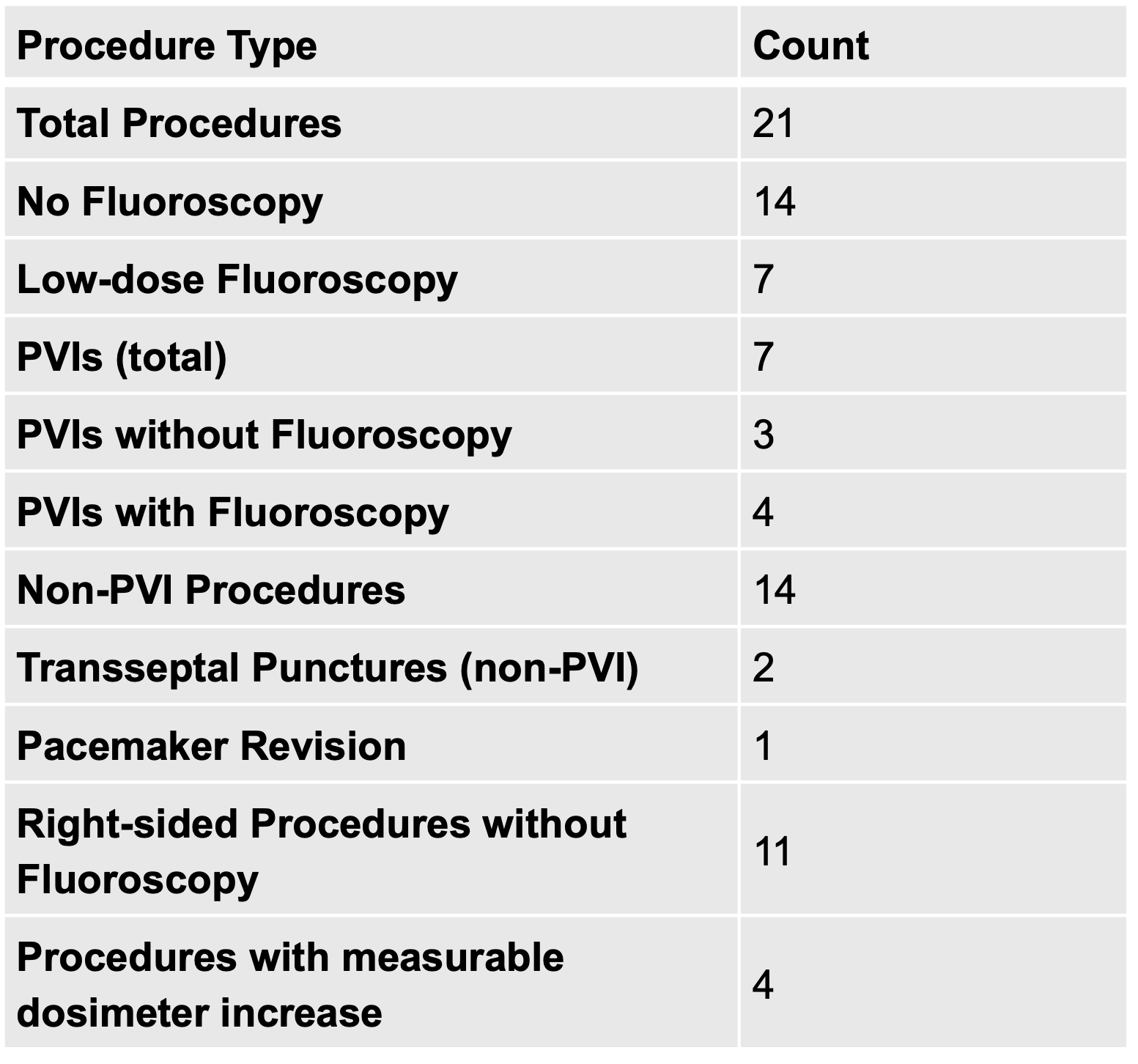

We retrospectively analyzed 21 consecutive EP procedures performed by a pregnant operator at Klinikum Fürth, Bavaria, Germany. Dosimeter readings (µSv) before and after each procedure determined net exposure. Variables included fluoroscopy use/time, dose-area product (DAP in cGy·cm²), procedure type, and patient factors. The operator wore a full-overlap 0.5 mm Pb apron, 0.5 mm thyroid collar, protective glasses, and used ceiling-mounted shields and table drapes. Optimal table positioning was consistently maintained. Most procedures used 3D electroanatomical mapping and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) to reduce or eliminate fluoroscopy. The Siemens Artis Zee system operated at 1 frame/second throughout.

Results:

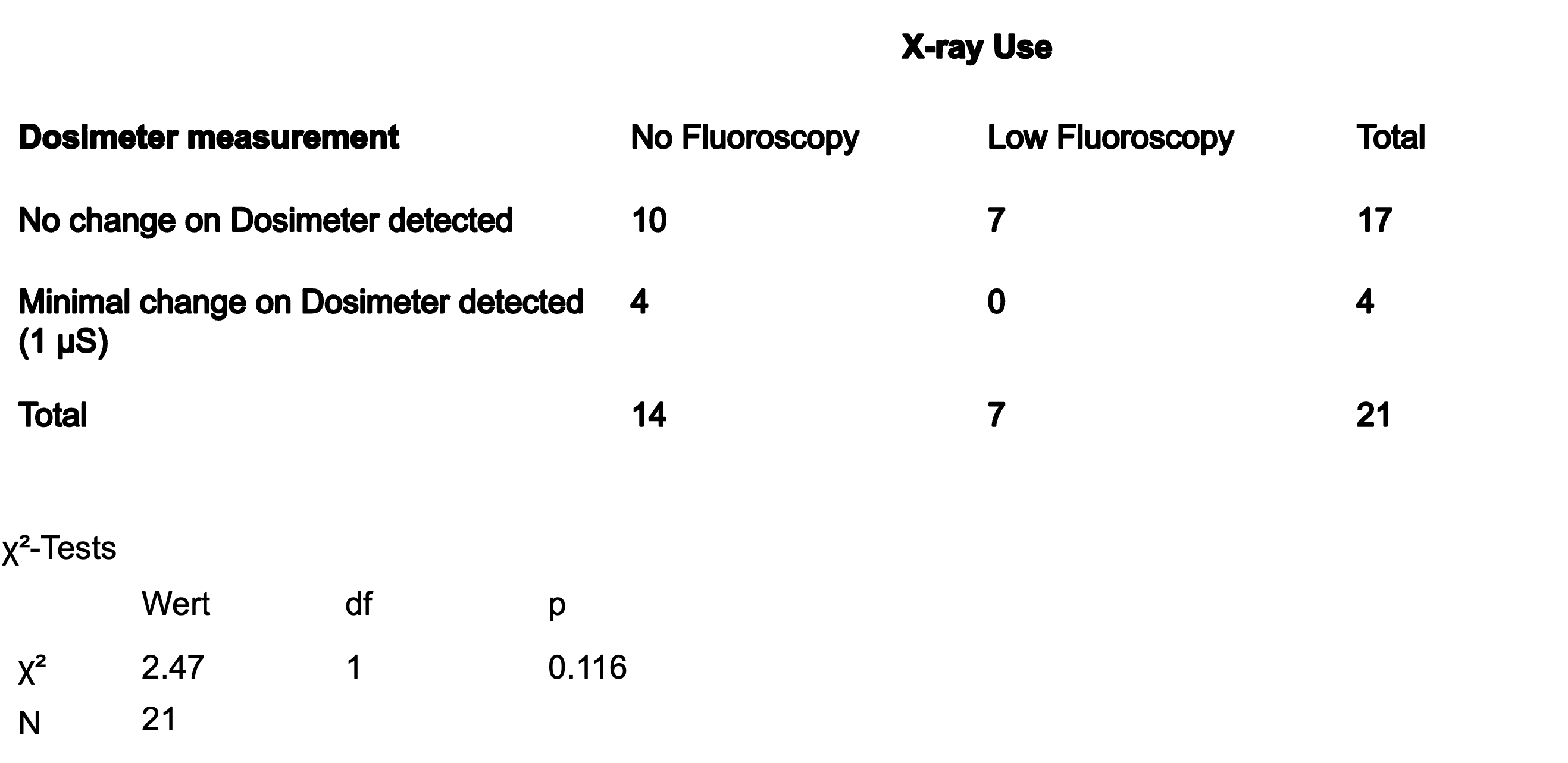

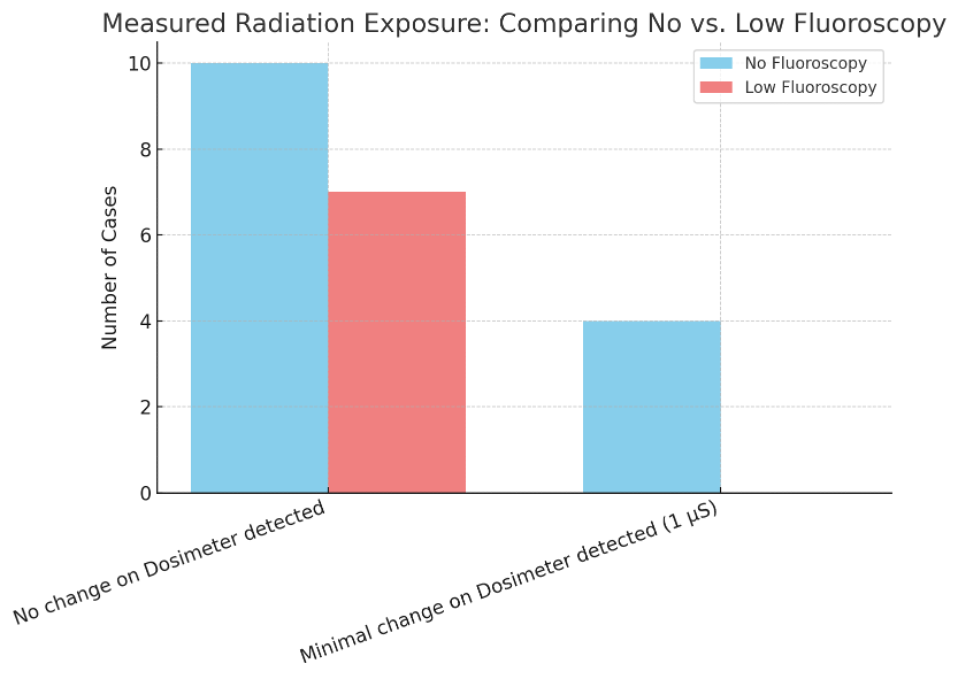

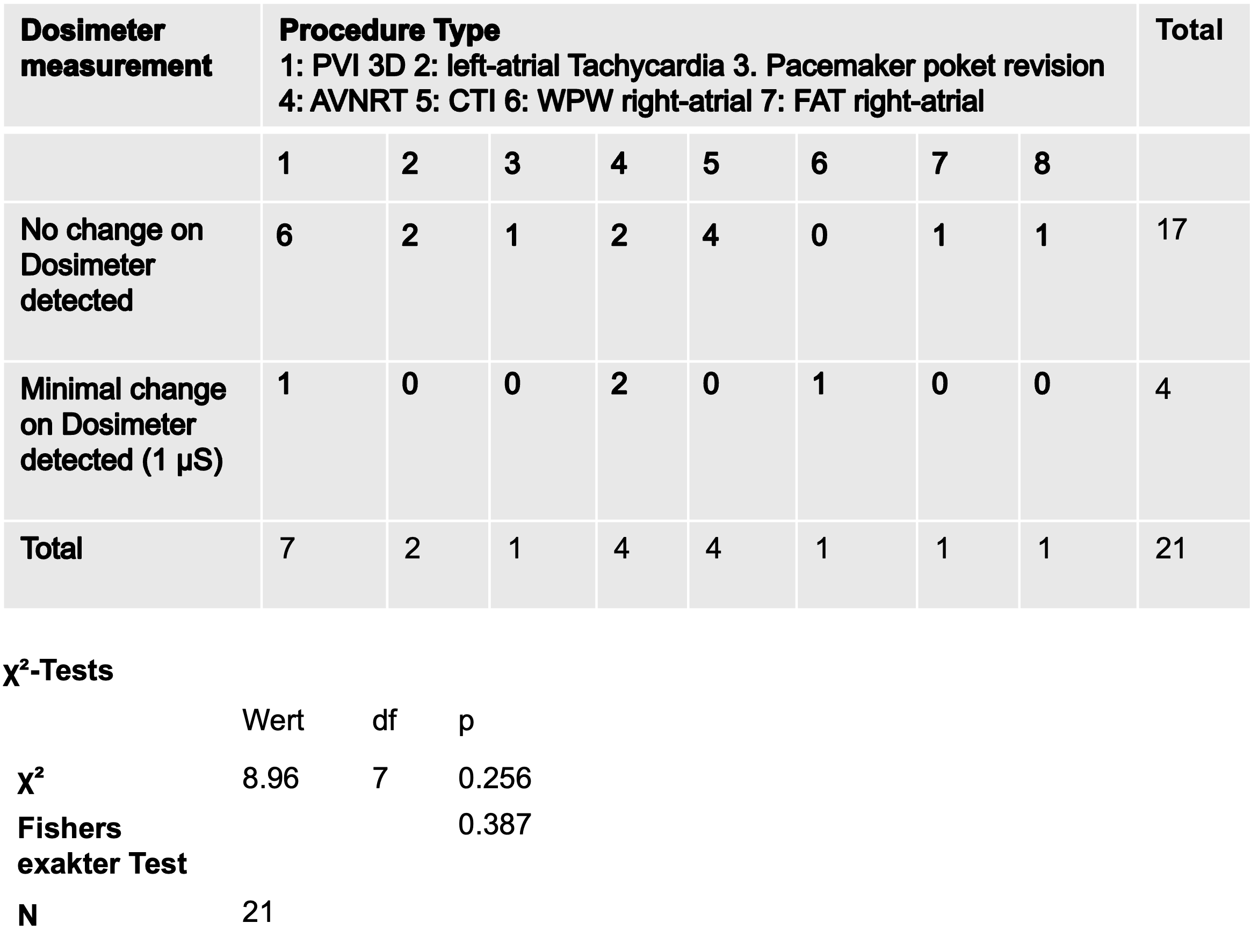

The maximum permissible cumulative fetal radiation dose during pregnancy is 1 mSv. During 21 procedures across the first two trimesters, the operator’s total occupational exposure was 149 µSv—well below this threshold, even when accounting for background radiation such as cosmic rays (~1 µSv/day). Of the 21 procedures, 14 were completed without fluoroscopy; the remaining 7 used low-dose settings. Among 7 pulmonary vein isolations (PVIs), 3 were fluoroscopy-free, 4 required low-dose fluoroscopy. Of 14 non-PVI procedures, fluoroscopy was used in only 3 cases: two left-sided ablations (WPW and atrial tachycardia) requiring transseptal puncture, and one pacemaker pocket revision. All right-sided procedures—including CTI ablation, AVNRT, and right atrial tachycardia—were completed without fluoroscopy. Dosimeter readings rose by 1 µSv in only 4 procedures. These increases did not correlate with fluoroscopy use, suggesting background radiation or dosimeter sensitivity. Chi-square analysis showed no significant association between fluoroscopy use and exposure (χ²(6) = 2.47, p = 0.116), procedure type and exposure (χ²(6) = 8.96, p = 0.25), or exposure and patient BMI or procedure recurrence.

Conclusion:

This study demonstrates that pregnant electrophysiologists can safely perform EP procedures in modern labs using no- or low-fluoroscopy techniques such as 3D mapping and TEE. Radiation exposure was minimal, infrequent, and unrelated to fluoroscopy use—likely reflecting background variability or dosimeter sensitivity. Despite limitations, these real-world data support that pregnancy need not be a barrier to professional activity in EP, advancing gender equity in a traditionally male-dominated field.