Patient presentation

A 60-year-old female with a history of symptomatic obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (oHCM) presented to our clinic with worsening dyspnea, classified as NYHA-Class III at the time of presentation. Beside the known oHCM, the patient suffered from bronchial asthma and arterial hypertension. The medication consisted of Bisoprolol 5 mg o.d. and Amlodipin 5 mg o.d.. Apart from a grade 3/6 systolic ejection murmur at the left upper sternal border, the rest of the clinical examination was unremarkable. Noteworthy was the absence of syndromic features, such as hypertelorism, low-set posteriorly rotated ears and a webbed neck.

Initial work-up

The initial ECG showed a sinus rhythm without any signs of left ventricular hypertrophy or repolarization abnormalities. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed severe concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, with a septal wall thickness (IVSd) of 19 mm, a normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve, which was associated with moderate insufficiency and obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOTO), The peak gradient was 61 mm Hg during the Valsalva maneuver. Blood tests indicated normal renal function but an elevated NT-proBNP level of 641 ng/L.

Diagnosis and management

While HCM is primarily caused by sarcomeric gene mutations, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) can also result from other conditions, including congenital syndromes, metabolic disorders, infiltrative diseases and neuromuscular diseases. Our extended evaluation included cardiac MRI, which revealed LGE-positive fibrosis at the inferior insertion of the right ventricle, accompanied by global fibrosis shown by prolonged T1 relaxation times, findings inconsistent with an infiltrative disorder. Taking into account all the aforementioned findings, sarcomeric HCM was established as our working hypothesis. After obtaining the patient’s informed consent, genetic testing was subsequently performed.

In accordance with the 2023 ESC Guidelines, we first uptitrated the beta-blocker dose to the maximal tolerated level—7.5 mg of bisoprolol o.d.—and reassessed the patient after four weeks.

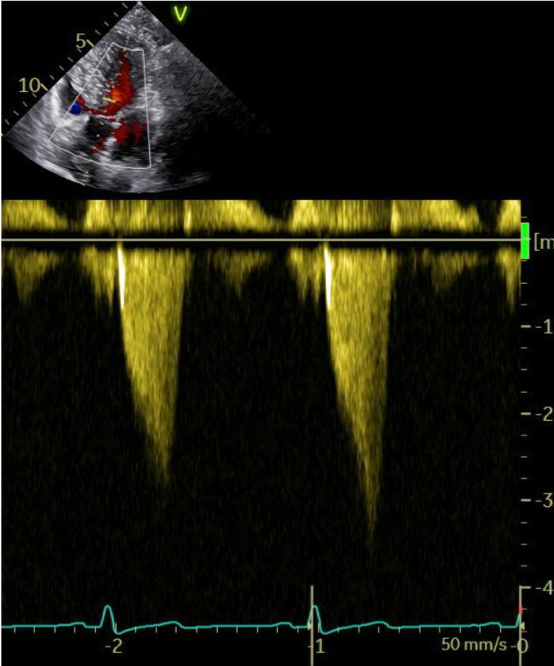

Because of a persistent elevated LVOT-gradient of 51 mmHg (Image 1a) and ongoing symptoms (NYHA-Class III), we decided to initiate additional treatment with the first-in-class myosin inhibitor mavacamten.

Follow-up

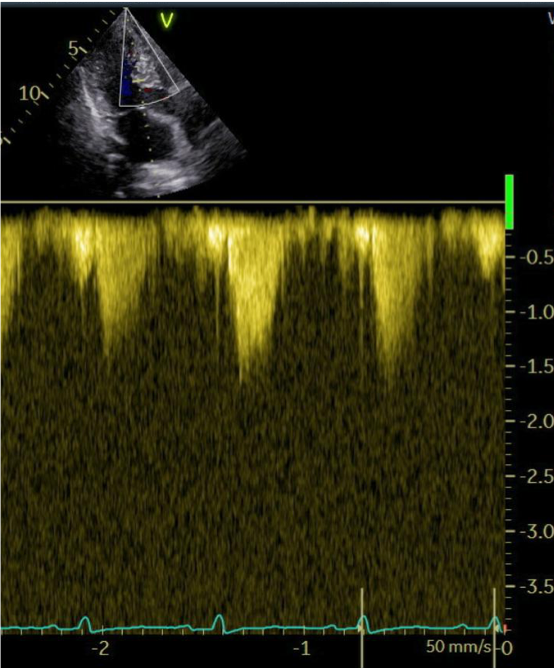

The patient was followed up every 4 weeks. A constant improvement of symptoms, echocardiographic findings and laboratory values was observed throughout the therapy. At the 6-month follow-up, dyspnea was classified as NYHA-Class II, the maximum LVOT gradient was 11 mmHg (Image 1b), and NT-proBNP notably decreased compared to baseline (202 ng/L).The systolic function of the left ventricle remained within the normal range. Seven months following the initiation of therapy with a myosin inhibitor, genetic testing revealed a positive result for a mutation consistent with Noonan Syndrome.

Conclusions:

This is the first documented case of treatment efficacy of myosin inhibitor therapy in NS-associated oHCM. Despite the distinct molecular mechanisms underlying hypertrophy in sarcomeric HCM and NS-associated HCM, the clinical improvement suggests that targeting downstream hypercontractility mechanisms can alleviate LVOTO, even in syndromic HCM. This finding underscores the need for further research to explore its potential application in RASopathy-associated HCM.