Background

Statin intolerance (SI) is frequent and associated with increased cardiovascular risk. Self-medication with supplements or over-the-counter drugs is widespread despite limited evidence on efficacy and safety. Patients with SI may be prone to self-medication to lower LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) and to treat statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS).

Methods

The Statin Intolerance Registry is an observational, prospective, multicentre study at 19 participating sites in Germany. Patients with SI were recruited 2021–2023. The use and predictors of self-medication are described in this analysis.

Results

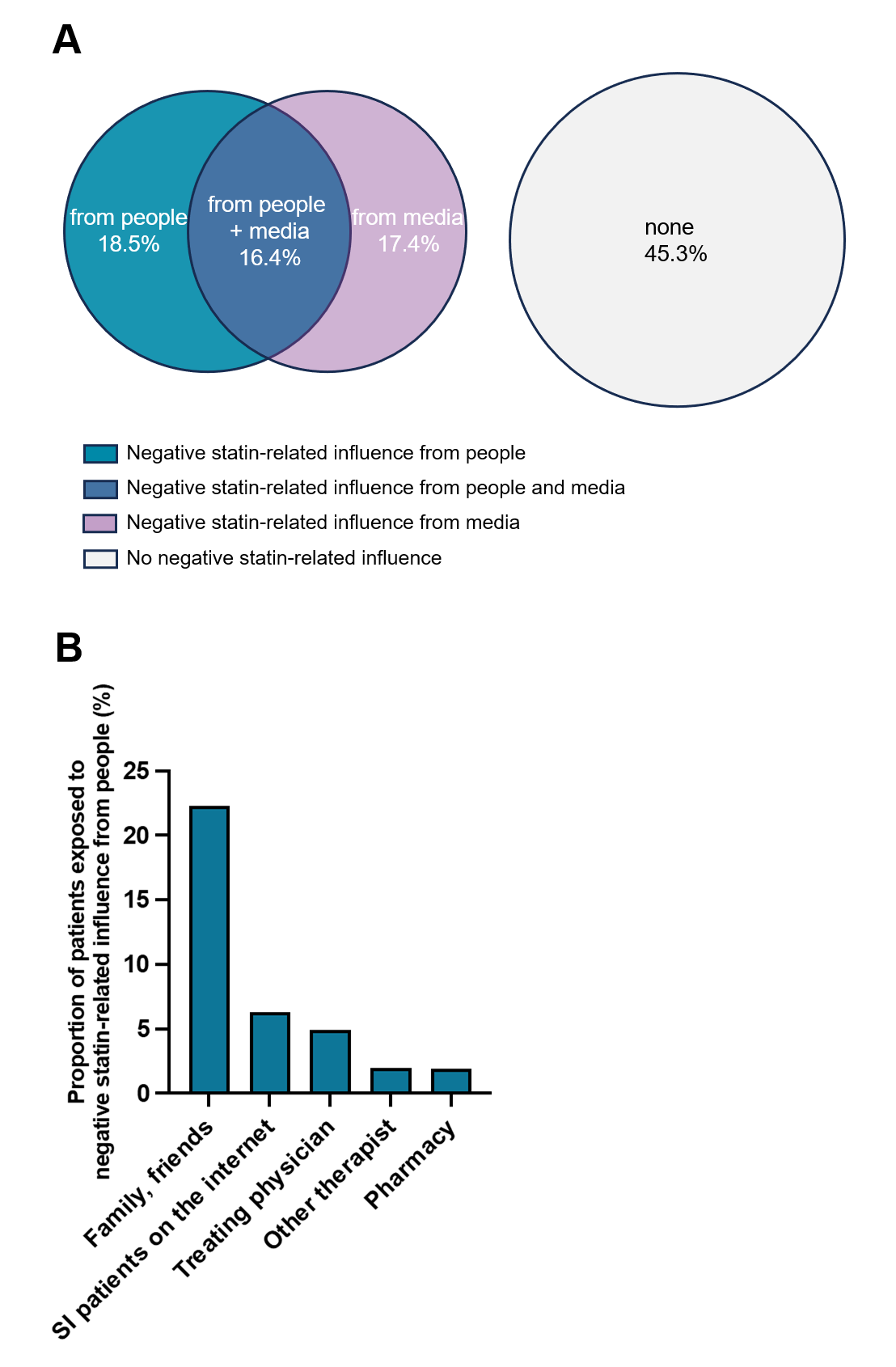

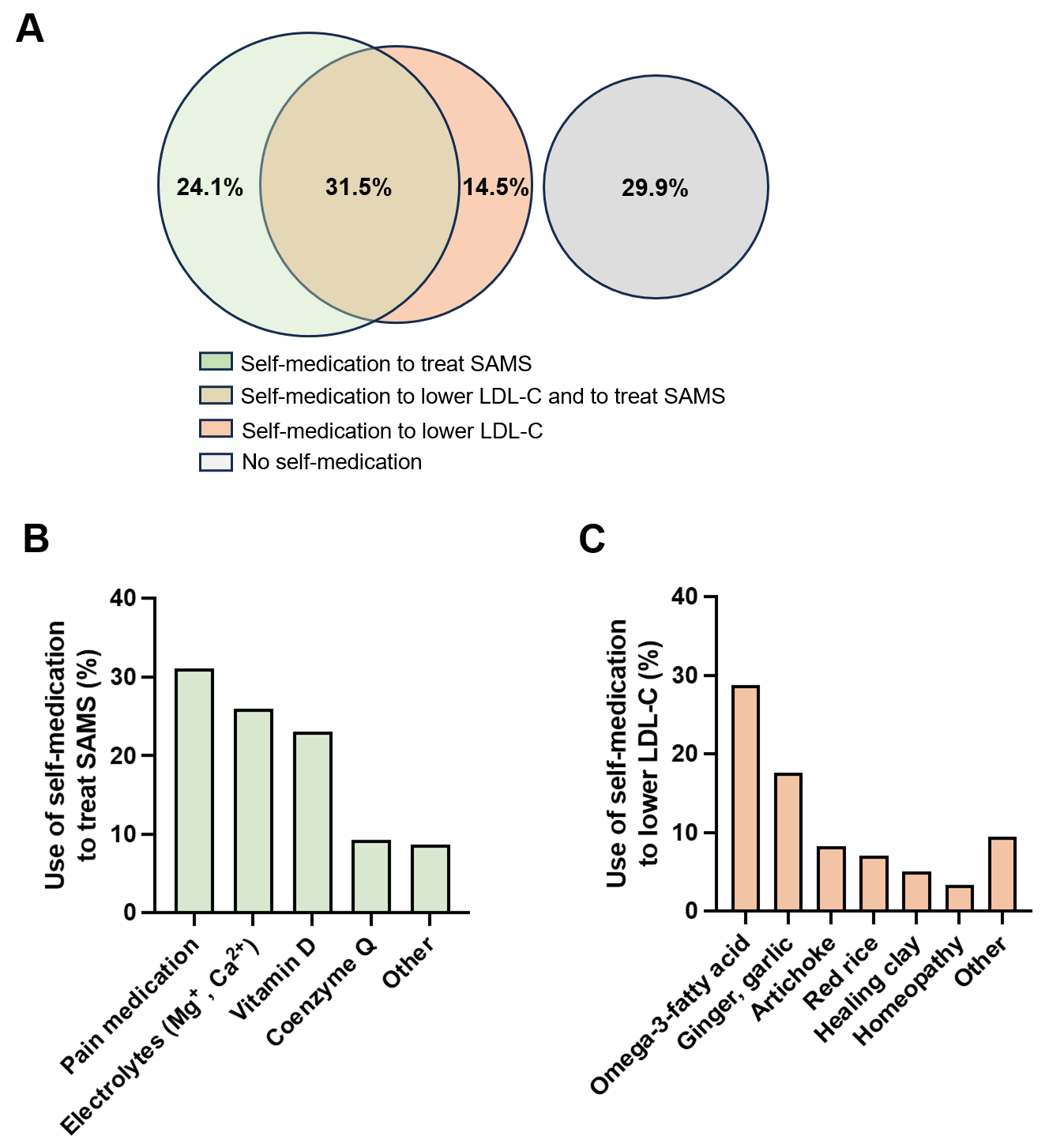

A total of 1,111 patients were included. The mean age was 66.1 (9.9) years, 57.7% were female. The majority of patients (88.0%) had ASCVD (Table). Among all patients, 70.1% reported use of self-medication to treat SAMS (24.1%), to lower LDL-C (14.5%), or to do both (31.5%) (Fig. 1A), corresponding to a total use of self-medication to lower LDL-C in 46.0% and to treat SAMS in 55.6% of patients. The most frequent self-medications used to treat SAMS were pain medication (31.1%), electrolytes (25.9%), and vitamin D (23.0%; Fig. 1B). The most commonly used supplements to lower LDL-C were omega-3 fatty acids (28.8%) and ginger/garlic (17.6%; Fig. 1C). Reporting self-medication was strongly associated with depressive symptoms (PHQ9 score) and experience of negative statin-related information. Use of self-medication to lower LDL-C was not associated with lower LDL-C levels. More than half (54.7%) of the patients reported negative statin-related influence from other people (mainly family and friends), the media, or both (Fig. 2). This was associated with more frequent self-medication but similar LDL-C concentrations.

Conclusions

The majority of patients with SI used self-medication to lower LDL-C or to treat SAMS. Self-medication was not associated with lower LDL-C levels. Proactive communication and education on the limited evidence on efficacy and safety of supplements may improve utilization of lipid-lowering medications with proven cardiovascular benefits.

Table

|

|

Total

(n=1111)

|

Self-medication

(n=747)

|

No self-medication

(n=364)

|

P

|

|

Demographic data

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age (years)

|

66.1 (9.9)

|

66.0 (9.7)

|

66.2 (10.9)

|

0.81

|

|

Female

|

57.7

|

61.2

|

50.3

|

0.001

|

|

Laboratory parameters (mmol/L)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total cholesterol

|

4.8 (1.7)

|

4.8 (1.7)

|

4.9 (1.7)

|

0.80

|

|

LDL cholesterol

|

2.8 (1.5)

|

2.8 (1.5)

|

2.8 (1.6)

|

0.72

|

|

HDL cholesterol

|

1.5 (0.5)

|

1.5 (0.4)

|

1.5 (0.5)

|

0.42

|

|

Triglycerides

|

1.8 (1.1)

|

1.8 (1.1)

|

1.8 (1.0)

|

0.43

|

|

Lipid-lowering agents

|

|

|

|

|

|

Established lipid-lowering therapy

|

83.4

|

83.7

|

82.8

|

0.72

|

|

Statin

|

26.9

|

24.9

|

31.0

|

0.03

|

|

Ezetimibe

|

39.2

|

36.3

|

45.1

|

0.005

|

|

Bempedoic acid

|

25.4

|

25.3

|

25.6

|

0.93

|

|

PCSK9 inhibitor

|

48.0

|

51.1

|

41.5

|

0.003

|

|

Cardiovascular risk factors

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hypertension

|

75.2

|

77.0

|

71.7

|

0.06

|

|

Diabetes

|

19.1

|

20.4

|

16.6

|

0.13

|

|

Active smoking

|

10.0

|

11.0

|

8.0

|

0.12

|

|

ASCVD

|

88.0

|

87.2

|

90.1

|

0.16

|

|

Comorbidities

|

|

|

|

|

|

Orthopedic disease

|

53.0

|

57.7

|

43.2

|

<0.001

|

|

Depression

|

10.3

|

12.1

|

6.6

|

0.005

|

|

Allergy

|

43.2

|

45.5

|

38.3

|

0.04

|

|

Chronic kidney disease

|

13.4

|

13.7

|

12.9

|

0.73

|

|

Psycho-social

|

|

|

|

|

|

EQ VAS score

|

64.8 (12.1)

|

62.6 (18.5)

|

70.0 (16.1)

|

<0.001

|

|

PHQ-9 score

|

5.8 (4.4)

|

6.4 (4.7)

|

3.4 (4.3)

|

<0.001

|

|

In committed relationship

|

73.5

|

77.0

|

66.5

|

<0.001

|

|

Higher education

|

20.6

|

21.6

|

18.7

|

0.27

|

|

Other parameters of interest

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intensity of muscle pain while on statin

|

7.0 (1.8)

|

7.1 (1.7)

|

6.7 (1.9)

|

0.001

|

|

SAMS-CI score

|

9.0 (1.8)

|

9.0 (1.8)

|

8.9 (1.9)

|

0.67

|

|

Expectation of adverse events on statin

|

6.0

|

7.1

|

3.9

|

0.03

|

|

Acquaintances with statin intolerance

|

36.6

|

42.4

|

23.9

|

<0.001

|

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2