https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-025-02625-4

Benedikt Köll (Hamburg)1, S. Ludwig (Hamburg)1, J. Weimann (Hamburg)1, L. Stolz (München)2, A. Scotti (New York)3, E. Xhepa (München)4, E. Donal (Rennes)5, D. Patel (Los Angeles)6, T. Tanaka (Bonn)7, T. Trenkwalder (München)4, F. Rudolph (Bad Oeynhausen)8, D. Samim (Bern)9, P. von Stein (Köln)10, C. Giannini (Pisa)11, J. Dreyfus (Paris)12, J.-M. Paradis (Quebec)13, M. Adamo (Brescia)14, N. Karam (Paris)15, Y. Bohbot (Amiens)16, A. Bernard (Tours)17, B. Melica (Espinho)18, O. De Backer (Copenhagen)19, Y. Lavie-Badie (Toulouse)20, M. Keßler (Ulm)21, C. Iliadis (Köln)10, S. Redwood (London)22, E. Lubos (Hamburg)23, M. Metra (Brescia)14, F. Praz (Bern)9, M. Gercek (Bad Oeynhausen)8, G. Nickenig (Bonn)7, T. Modine (Bordeaux)24, J. Hausleiter (München)2, A. Coisne (Lille)25, D. Kalbacher (Hamburg)26

1Universitäres Herz- und Gefäßzentrum Hamburg

Klinik für Kardiologie

Hamburg, Deutschland; 2LMU Klinikum der Universität München

Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik I

München, Deutschland; 3Montefiore-Einstein Center for Heart and Vascular Care, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

New York, USA; 4Deutsches Herzzentrum München

Klinik für Herz- und Kreislauferkrankungen

München, Deutschland; 5Univ Rennes, CHU Rennes

Rennes, Frankreich; 6Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

Los Angeles, USA; 7Universitätsklinikum Bonn

Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik II

Bonn, Deutschland; 8Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW

Allgemeine und Interventionelle Kardiologie/Angiologie

Bad Oeynhausen, Deutschland; 9Inselspital - Universitätsspital Bern

Universitätsklinik für Kardiologie

Bern, Schweiz; 10Herzzentrum der Universität zu Köln

Klinik III für Innere Medizin

Köln, Deutschland; 11S.D. Emodinamica, AOUP - Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Pisana

Pisa, Italien; 12Cardiology Department, Centre Cardiologique du Nord

Paris, Frankreich; 13Quebec Heart & Lung Institute, Laval University

Quebec, Kanada; 14University of Brescia, Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory and Cardiology, ASST Spedali Civili and Department of medical and surgical specialties, radiological sciences and public health

Brescia, Italien; 15Cardiology Department, European Hospital Georges Pompidou

Paris, Frankreich; 16Department of Cardiology, Amiens University Hospital

Amiens, Frankreich; 17Cardiology Department, CHRU de Tours

Tours, Frankreich; 18Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia

Espinho, Portugal; 19Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University Hospital Copenhagen

Copenhagen, Dänemark; 20Department of Cardiology, Rangueil University Hospital

Toulouse, Frankreich; 21Universitätsklinikum Ulm

Klinik für Innere Medizin II

Ulm, Deutschland; 22Department of Cardiology, St. Thomas' Hospital

London, Großbritannien; 23Katholisches Marienkrankenhaus gGmbH

Kardiologie und Angiologie

Hamburg, Deutschland; 24Service Médico-Chirurgical: Valvulopathies-Chirurgie Cardiaque-Cardiologie Interventionelle Structurelle, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Bordeaux

Bordeaux, Frankreich; 25Department of Clinical Physiology and Echocardiography - Heart Valve Clinic, CHU Lille

Lille, Frankreich; 26Universitäres Herz- und Gefäßzentrum Hamburg

Allgemeine und Interventionelle Kardiologie

Hamburg, Deutschland

Background

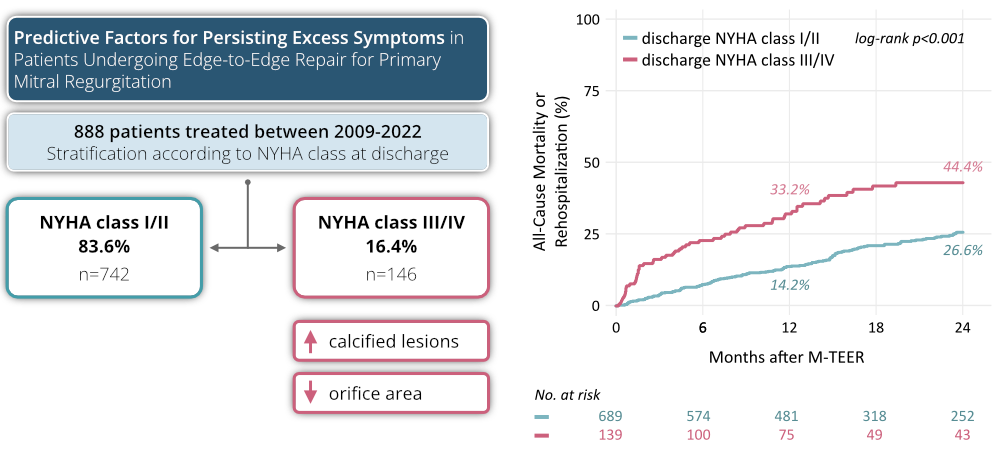

Residual mitral regurgitation (MR) post transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (M-TEER) is a strong indicator of adverse events in patients with primary MR (PMR). While M-TEER generally improves MR, a subgroup continues to experience a substantial symptomatic burden, shown by New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV status at discharge. Identifying predictive factors for these persistent symptoms can improve patient selection and post-procedure strategies. This study leverages data from the PRIME-MR registry to identify predictors of persistent symptom burden post M-TEER.

Methods

PRIME-MR is a retrospective, investigator-initiated registry including PMR patients who underwent M-TEER at 24 high-volume centers from 2009 to 2022. After excluding in complete cases, 888 patients were analyzed. Symptomatic status at discharge was classified as NYHA Class I/II or Class III/IV, with the latter indicating symptom persistance. The primary composite endpoint was all-cause mortality or rehospitalization.

Results

Among the 888 patients, 742 (83.6%) achieved NYHA Class I/II, while 146 (16.4%) remained in NYHA Class III/IV. Both groups were similar in age and sex distribution. However, those patients with persistent symptoms had higher initial NYHA classes (NYHA Class ≥III: 93.8% vs. 81.6%; p<0.001) and a shorter 6-minute walk distance (median 158 m [IQR 40, 270] vs. 252 m [137, 329]; p=0.006). Baseline MR severity (median EROA 0.4 cm² [0.3, 0.6]) did not differ ( p=0.81), but symptomatic patients had higher rates of mitral annular calcification (7.1% vs. 2.7%, p=0.023) and a smaller mitral valve orifice areas (4.0 cm² [3.1, 5.2] vs. 4.9 cm² [4.0, 5.8]; p=0.001). Moderate or greater residual MR at discharge was more frequent in symptomatic patients (56.6% vs. 28.9%; p<0.001) and linked to higher all-cause mortality or rehospitalization rates within 2 years (log-rank p<0.0001, Figure 1).

Conclusion

A distinct subset of patients undergoing M-TEER for primary MR does not experience symptomatic improvement at discharge, particularly those with mitral annular calcification and smaller mitral valve orifice areas. This subgroup was at significantly higher risk for mortality or rehospitalization. Tailored risk assessment and management strategies are crucial for improving outcomes in these high-risk patients.